A brief history of the workhome

The building type that combines dwelling and workplace has existed in a multitude of different forms for hundreds, if not thousands, of years. But, strangely, very little has been written about it. It seems to have resisted collection and classification. Carl Linnaeus, the great eighteenth century Swedish botanist whose classification system for the biological sciences is still in use today, said: “Without a name, the knowledge of an object is lost”. This may be key.

Until the industrial revolution, it was in almost universal use, called ‘house’, with sub-sets of ale-house, bake-house etc. But through the twentieth century the term ‘house’ gradually came to mean a building in which we cook, eat, sleep, bathe and watch TV, nothing more. And as a result the building that combines dwelling and workplace became nameless.

Until, that is, the term ‘live/work’ was coined in the 1970s, generated as part of a highly successful branding exercise for loft developments in SoHo, New York. These were marketed as an innovative building type that facilitated an exciting new lifestyle. But nothing could have been further from the truth. Home-based work was the norm until and beyond the industrial revolution, and the ‘live/work’ unit was merely the latest incarnation of an age-old building type. However, in the absence of any other name, ‘live/work’ has gradually begun to be used as a generic term for buildings that combine dwelling and workplace. This is problematic as the term is still closely associated with the loft-style apartment. It does not sit easily with the wide range of other dual-use buildings such as the pub, the vicarage, the corner shop, the workshop or office in the house or at the bottom of the garden, or the studio-house. These and many others have therefore tended to be ignored in discussions of ‘live/work’.

The need for terminology

In order to be able to take an overview and think analytically about this old but neglected building type, it has become clear that a new term is needed, one that describes all the buildings that combine dwelling and workplace in the same way that the word ‘dwelling’ describes all the buildings we live in, from igloo to palace, and the word ‘workplace’ describes all the buildings we work in, from coal-mine to theatre. We have coined the term ‘workhome’, simple and clear.

This might be thought to be merely a rather obscure corner of architectural investigation. But in fact this dual-use building type has immense contemporary relevance and potential. Home-based work is a popular working practice that offers many social benefits. It improves the work/life balance for parents, allowing them to work flexibly, interweaving the care of their children. It enables the elderly, sick and disabled to remain economically active. It has a positive impact on the city, contributing to the development of community social networks and creating busier, and therefore livelier and safer, cities, towns and villages. It is good for the economy at both the macro [corporation] and the micro [start-up/ small business] scale. It is also good for the local economy; home-based workers tend to use local services. But maybe its most important benefit to society is its inherent environmental sustainability. By reducing commuting it reduces carbon emissions and takes pressure off our overstretched transport infrastructure.

In short, it offers a potential solution to many of today’s pressing problems. In order to understand how we may design for this working practice today it may be useful to know something about this old but neglected building type's history.

The English workhome in history

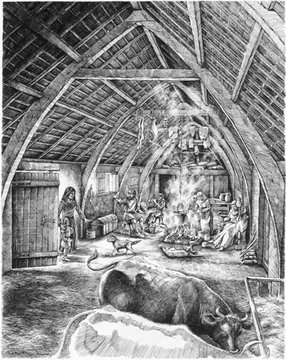

In England before the industrial revolution, almost everyone inhabited workhomes. The longhouse was a single-storied rectangular building occupied by medieval peasants in areas of England where animals needed to be inside at night and in winter [image 1]. The animals lived at one end and the people at the other. All the functions of every day life were carried out in and around in this single open-plan space. It was a combination of kitchen and spinning/ weaving/dressmaking workshop, bedroom and dairy, dining room, butchery, tannery and byre.

The medieval English gentry and their servants lived and worked together in castles and manor houses. On feast days five hundred or more people might be entertained in these workhomes. Armies of peasants worked in the fields to provide the basic ingredients, and swarms of servants in the kitchens to prepare the meals. The household ate together in the central hall. Afterwards the servants cleared the trestle tables and slept on the rush-covered floor around the fire or in their workrooms. The noble family had separate sleeping quarters. Every few weeks the hall transformed into a courtroom, presided over by the lord, where rents were set, disputes mediated and offenders punished.

Medieval merchants’ and craft-workers’ workhomes had a shop or workshop onto the street where goods were made and sold. Trading and family life, public and private, were combined in a few multi-purpose spaces. Customers ate and drank with family members in a central, double-height hall; important deals were made in a small rear room. The family, apprentices and servants slept in the hall, shop/workshop or one of the smaller rooms on an upper floor.

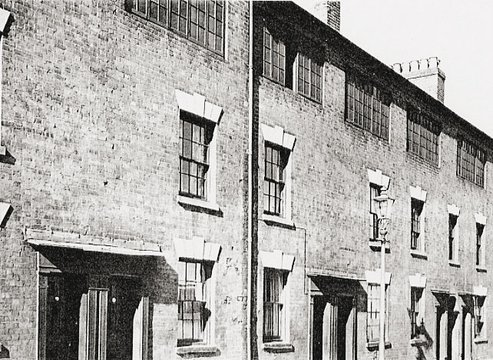

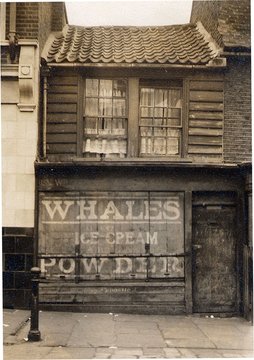

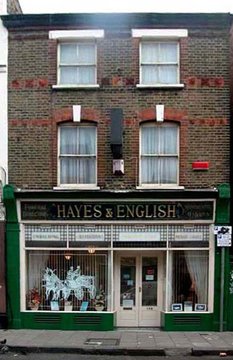

The workhomes of seventeenth and eighteenth century silk-weavers, watchmakers and stocking-knitters had workshop spaces with large windows to provide the high levels of natural light necessary for their trades. Many of these buildings still exist today. They can be identified by their combination of unusually large and domestic scale windows [image 2]. These buildings took different forms depending on the status of the craft-worker. Master weavers’ workhomes often had two floors of elegant residential accommodation below garret weaving lofts where their employees worked [image 3]. Weavers running small businesses often had workhomes with loom-shops on several floors [image 4]. The family lived and worked in these buildings with employees and apprentices, the latter tending to sleep amongst the looms. The poorest weavers, working by the piece for a master weaver, inhabited small workhomes with a living space on the ground floor and a space for a single loom, lit by a large window, above [image 5, 6].

In Coventry this type of workhome, generally inhabited by silk-weavers or watchmakers, was called a ‘top-shop’ because the highly glazed workshops were positioned under the roof to make the most of the natural light [image 7]. The cottage factory consisted of a terrace of top-shops with a steam engine at one end, a single driveshaft linking power-looms in the individual weaving lofts [image 8, 9]. This meant home-based weavers could compete with factory-based weavers while maintaining the benefits of home-based work.

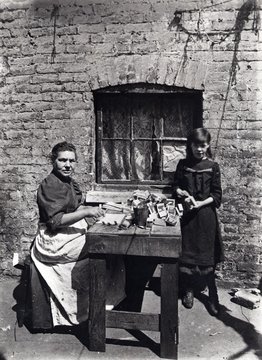

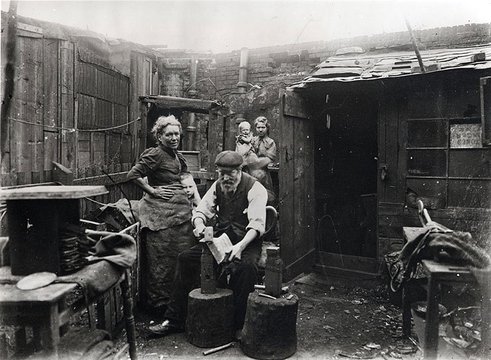

People often think that in the industrial revolution the working classes went out to work in mills and factories while the middle classes commuted from the suburbs to work in the City. While this is true, what is less known is that a large proportion of the working population continued in home-based work. Many familiar Victorian workhomes still exist all around us in our cities, towns and villages, including pubs [image 10], shops [image 11] and funeral parlours [image 12] with living accommodation above, school caretakers’ houses embedded in schools [image 13] and fire-stations that incorporated fire-fighters’ living accommodation [image 14]. In the late nineteenth century, the yards and courts of the East End of London teemed with home enterprise [image 15, 16, 17, 18], while numerous professionals, managers and clergy lived at their workplaces [image 19, 20]. Both self-employed craft-workers and proprietors of small businesses set up workshops where they could make goods, either in their workhomes or in the associated back yards, where they worked with family members and employees.

The modern workhome

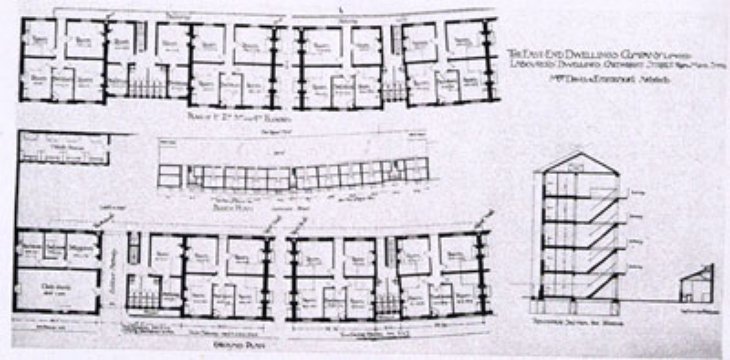

At the turn of the century, however, social reformers decided home-based work was undesirable. In some cases this was clearly true. ‘Fur-pullers’ removed fur from untreated hides in the spaces they also lived in, and often became seriously ill and died young as a result. But in most cases the work had no detrimental effect on the home apart from increasing an existing problem of overcrowding. In fact there is some evidence that it had a beneficial effect on the neighbourhood. Nevertheless, slum clearances destroyed the buildings, courts and yards that had allowed people to work from home, and new ‘Model Dwellings’ replaced them that were not conducive to home-based work [image 21, 22]. Tenancy agreements in the new buildings prohibited home-based work of any sort.

Simultaneously, Ebenezer Howard introduced the idea of the Garden City, which revolved around functional zoning. This was adopted with zeal in newly formulated governance systems for the planning and taxation of the built environment. Through the twentieth century new housing was built in residential estates that were segregated from both commercial and industrial zones. Tenancy agreements that prohibited home-based work were universally adopted in social housing. By the mid 1950s the practice of home-based work was in decline, with the majority of households supported by a single male breadwinner who went ‘out to work’. The remaining home-based workers fell into one of two camps: either the ‘backbone of the community’, the vicars, bakers, garage or fish and chip shop proprietors, the shopkeepers, school caretakers etc, or the unregulated pieceworkers, often female and ethnic minority, working for cash for exploitative employers. The former tended to inhabit historic workhomes, while the latter appropriated space, often illicitly, in their dwellings. Briefly, during the mid-twentieth century, we more or less stopped designing and building workhomes.

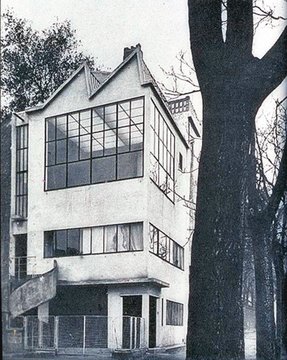

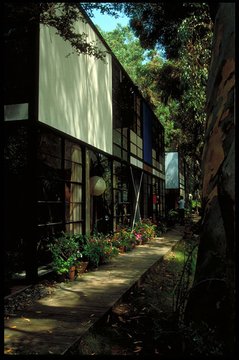

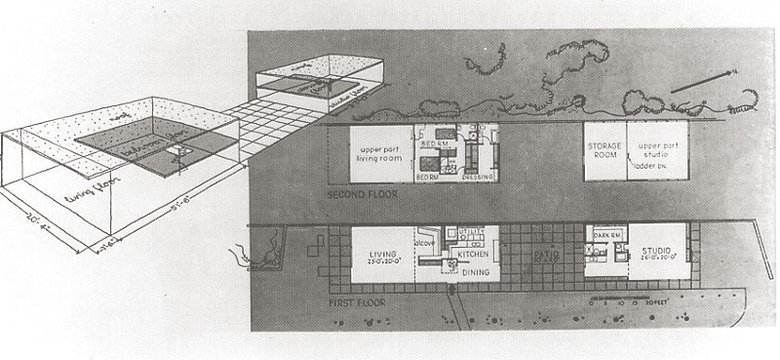

Workhomes are not just a vernacular phenomenon, however. They can be found throughout architectural history, usually disguised as houses or workplaces of some sort, as well. Many examples were built throughout the twentieth century. Three iconic buildings provide good examples: Ozenfant's Atelier by Le Corbusier, the Maison de Verre by Bernard Bivjoet and Pierre Chareau and the Eames House by Charles and Ray Eames. They loosely correlate with the workhoime 'Spatial Design Strategy' typology. The Maison de Verre [Paris, France 1932] is a classic 'live-with' workhome [image 23], consisting of ground floor consulting rooms for a gynaecologist with two floors of living accommodation above. The single front door has a triple doorbell: for 'docteur', 'visiters', and 'service'. Each bell makes a different sound, to enable the correct person to answer the door [image 24]. In the workhome designed for painter and sculptor Amedee Ozenfant [Paris, France 1922], a double-height studio with vast areas of glazing to both walls and roof, sits above two floors of domestic accommodation [image 25]. Separate entrances for artist and members of the public make it a 'live-adjacent' workhome. The Eames House [Los Angeles, USA 1949] consists of two buildings, a dwelling element and a studio element. Separated by a small courtyard, they use the same structural and constructional language and the same spatial formula, of double height space with mezzanine: 'live-nearby' [image 26].

The ‘invention’ of ‘live/work’ in the late twentieth century exposed an apparently new market for workhomes. Inspired by artists living and working in Manhattan lofts, dual-use spaces, often double height and open-plan like the medieval longhouse, were designed for people engaged in home-based work in the creative industries [image 27, 28]. The popularity of this building type was widespread, innovations in telecommunications and information technology making it possible for people in a wide range of occupations to live at their workplace or work from home. An explosion in ‘live/work’ development ensued with developers in the UK and elsewhere making large profits as buildings on land zoned [and therefore priced] light industrial were sold for almost residential prices. Controversy raged. Planners, particularly, were outraged at what appeared to be a way of making a fast buck by building housing on light-industrial land. So, after a brief boom, planners clamped down on ‘live/work’ policy and permissions, blocking the widespread development of this form of workhome.

In her 2007 PhD [‘The workhome… a new building type?’], Frances Holliss uncovered the history of the workhome in the UK from medieval times to the present day, as a way of establishing the existence of this old but neglected building type. The Workhome Design Guide has been created through an Arts and Humanities Research Council [AHRC] funded Knowledge Transfer project; its aim is to disseminate the findings of the doctorate to the public realm. We think the workhome is a building type with the potential to transform the Western city.